Is Virtual Reality the ultimate empathy machine?

Several years ago, while working on a project for the International Rescue Committee, I learned that non-profit organizations were starting to use VR technology to engage prospective donors and connect them to the cause. I wondered, can it also have long-term benefits for the way we care about each other?

Virtual reality (or VR) uses technology to immerse users in places and experiences. Some argue that it can also allow us to see the world from another person’s perspective, as Chris Milk described in his TED talk about “the ultimate empathy machine”. To be honest, when I first heard about VR many years ago I was unconvinced. My first experience actually using it was at a meetup in Boston where I got to virtually experience a recording studio. I remember feeling vaguely queasy, but also loved traveling to this world I’d always been curious about.

Soundstage VR allowed me to build my own virtual music studio, play several instruments in a virtual space and mix and sample music. While I’d never had aspirations to become a music producer or work in a sound studio, interacting with virtual knobs and sliders gave me an incredible insight into what this experience might be like. Although I felt self-conscious wearing this giant headset and waving “digital wands” around, I couldn’t help wondering whether this would become much more commonplace in the future.

Source: Soundstage VR

Source: Soundstage VR

VR offers a new canvas for storytelling

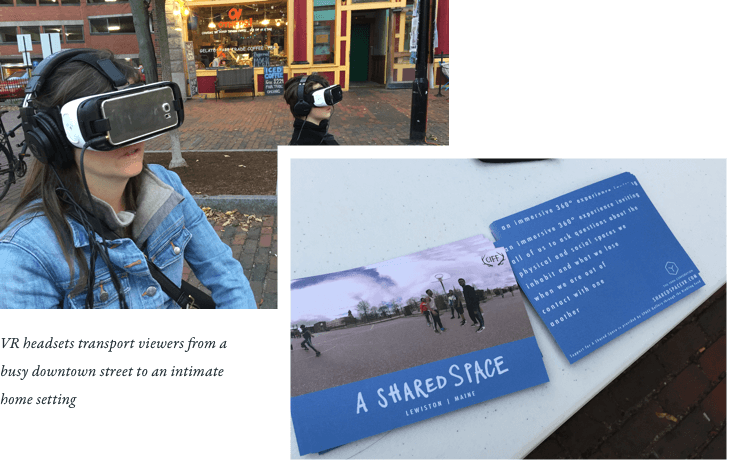

My next experience using VR came a few months later, where I was able to “sit” in the living room of a new immigrant family and hear shared stories of ways they’d struggled to settle into life in Maine after leaving one of the largest refugee camps in the world in Syria. “A Shared Space” offered me a glimpse into the lives of people who live close to me in Portland, Maine but whose experience of living in one of the least diverse states in the country is radically different from mine. Yet again, I was moved by the power of VR to transport me somewhere else, though this time the experience was more intimate, more about storytelling than technology.

I was fascinated to learn that a truly immersive VR experience is stored in a different part of the brain, and saved as a memory as opposed to simply a viewing experience. Brain imaging studies conducted at Peking University utilized functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), to capture the increased activation triggered when subjects looked at painful images in VR. These images show how the brain is tricked into actually feeling the virtual experience, directly affecting the neural substrates. This means that VR has the potential to be an incredibly powerful medium to evoke empathy and elicit action.

VR has opened a new frontier in fundraising by immersing potential donors in faraway worlds and situations that are often difficult to empathize with or imagine.

Utilizing VR for positive impact

The use of VR was still relatively limited when I worked with the International Rescue Committee, but in the years since more non-profits have found ways to connect this technology to their missions. The United Nations worked with VR filmmaker Chris Milk to produce Clouds Over Sidra, which portrays the experience of a 12-year-old girl, Sidra, living in a Syrian refugee camp. The VR film, which was shown at UNICEF’s annual fundraising conference helped to raise $3.8 billion; with one in six people donating after experiencing the virtual reality documentary—twice the charity’s normal rate.

SmileTrain is another example of a non-profit that has used this medium to help potential donors connect viscerally with those affected. SmileTrain’s mission to help thousands of children in developing countries with cleft palate repair surgeries, and “change the world, one smile at a time.” This VR film portrays Nisha’s journey as she leaves her remote village to have the surgery, then returns to her family, bursting with new hope for education, marriage and children of her own - a future that prior to this operation was out of reach.

The final example I’d like to share is closer to home. Southern Maine Hospice is an incredible local organization that I have experienced first hand. After my mother died very suddenly, they welcomed me and offered a safe place to grieve with others also experiencing the loss of a loved one. I recently learned that hospice staff are being trained on a virtual reality simulation that depicts care from a patient’s perspective. It follows Clay, a 66-year old cancer patient from the moment of first diagnosis through end-of-life. I was my mother’s caregiver as she went through a very similar journey, also battling cancer and also 66 when she died. I wish I’d had the experience these caregivers are having before going through what I experienced, so that I could have been stronger and more prepared for what would come. I’m not sure it would have made the feeling of loss any less intense, but it might have helped me better navigate treatment, hospice, and the turbulence of family that accompanies caring for a loved one approaching death.

Can VR have a long-term impact on empathy?

Imaging has proven that VR literally changes our brains. The lingering question that I have is whether it can have a long-term, positive impact, turning us into more empathetic individuals? For more than 10 years, a Stanford lab has been researching this very question and is about to embark on their most ambitious project yet, a study that will track how virtual reality affects empathy in 1,000 diverse volunteers.

It will be interesting to see whether certain individuals are more impressionable than others, and whether age, ethnicity, social or economic status positively or negatively pre-dispose a research subject to becoming more empathic through VR. And how long do the effects of VR last? Are those individuals who were inspired to donate to specific causes after being immersed in a VR experience equally as committed a year down the road? These are all important questions that Jeremy Bailenson, who is heading up the research at Stanford, will be investigating. As there are no longitudinal studies yet on the long-term effects of VR, Bailenson hopes that this study will provide some important insights and give us a better understanding of what this medium is truly capable of. I’m excited to see VR evolving beyond the world of video games, towards a broader role meaningfully connecting humans with each other and being used to make a difference in the world.