Minimum Lovable Products (MLPs) require tough parents

Most startups and new product developers focus first on releasing a Minimum Viable Product with minimal features. In fact, some go so far as to say that if your product is too evolved when you first release it, you’ve invested too much. This is where thinking of your first-born product as “minimally lovable” can be very powerful.

To answer this question, it makes sense to first unpack what a Minimum Viable Product (or MVP) is. The iPhone - now more than a decade old- provides a very relatable example of a product whose initial feature set was considered to be minimally viable. When it was first released in 2007, the iPhone was incredibly disruptive, but had only a fraction of the features that it does today. What made it most distinctive was that it didn’t have a physical keyboard and it allowed people to fully access the internet.

Positioning the phone as a platform for apps was a radical innovation, and gave Apple something to take to customers and test in the marketplace. The hypothesis was that customers would be excited by a single device that would carry music, make calls, send messages and more. The exponential growth in iPhone sales over the past 12 years affirms that their hypothesis was correct!

An MVP is a down payment on a larger vision.

Yes, beauty does matter.

An MVP doesn’t need to be the smallest possible product, made the cheapest possible way, in the shortest amount of time. An MVP is a product with just enough features to satisfy early customers and provide feedback for future product development. It should act as a catalyst to spark conversations about what could be better.

The problem is, many MVPs disappoint their early users, who despite the marketing hype, fail to see the appeal of the product they’ve been sold. In other words, while it’s minimal feature set does indeed function, the overall experience does not spark joy in any way.

Often visual aesthetics, micro-interactions, and elegant design are seen as superfluous and intentionally de-prioritized. Sadly, these MVPs feel soulless and well…unloveable. They do what they are supposed to do, but they don’t inspire us to pick them up repeatedly and make them our next best digital friend. I’d argue that the first iPhone was more than an MVP. It was actually an MLP that moved people, made them happy and was truly appealing from the beginning. It was also beautiful.

How can you be sure you’re building an MLP?

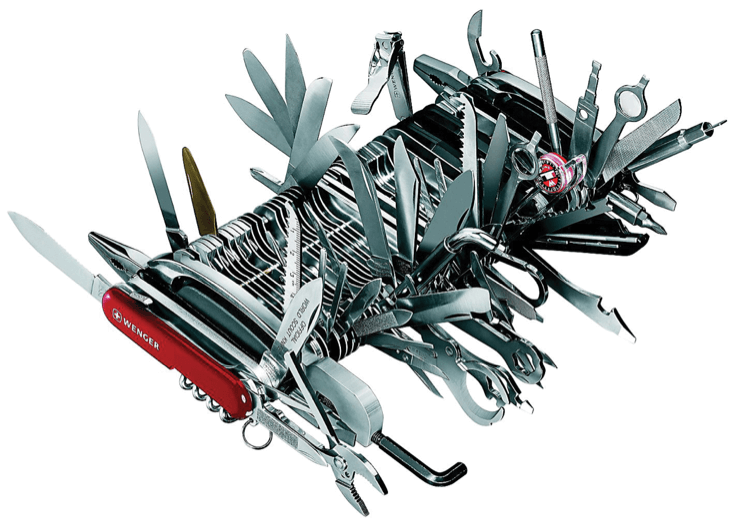

If you’ve done some foundational research, you’re clear on user needs and behaviors, and also on the competition you’re facing. Ideally, before starting to build anything, you’ve also done some iterative design and taken an early clickable prototype to a small group of potential users to solicit feedback. Likely, you’ve already learned that some of the features you’ve included aren’t essential, and may even take away from the core product experience. Hopefully, your MVP doesn’t resemble this:

To be an MLP, your product should include a couple of the top features and be beautifully designed. Of course, it must also be technically robust, as there is nothing worse than something that looks great but doesn’t work. If your product is for consumers as opposed to B2B, in addition to more traditional news coverage, reviews from early adopters in the app store and Google Play will matter. Increasingly we are a society that relies on reviews and ratings to help us make decisions - where to eat, what to buy, who to like. Because there are now millions of apps competing for our attention, standing out and being lovable has become tougher than ever.

While the number of downloads is an important metric, usage statistics are a better indicator of what people really find valuable. Interestingly, while the average person now has around 80 different apps installed on their phone, only 9 of those apps see daily use [1). To summarize, the MVP helps provide insights on the most important features. The MLP, in contrast, is intended to make a small number of users passionate about the product who will become early advocates.

It’s better to build something that a small number of users love, than a large number of users like.

Showing tough love

Agreeing on the “top” features that will make it into an initial product release is not easy. Even when armed with data, there is often a disconcerting feeling that perhaps users couldn’t yet “see the potential”. One of my favorite scenes from the series “Mad Men” is a scene between Don Draper and a market research consultant. She tells him what the focus group findings are, to which he responds “A new idea is something they don’t know yet, so of course it’s not something that comes up as an option.” I saw this first hand when doing user research on online dating platforms many years ago - the idea was so novel, that many people were very dubious about it ever catching on. And how many people were initially afraid to buy anything on the internet, worrying that their financial information would be stolen?

Running an “MLP Workshop” has been a great way to get “parents” of a product to agree where to focus first. On the wall we have three large signs – “MUST,” “SHOULD,” and “COULD” – and all potential user stories are printed on index cards in advance. The corresponding category, or epic, as well as a developer’s story point estimate are also on the individual cards, ensuring that technical feasibility, as well as business priority and user desirability are part of the decision-making equation. Usually, these MLP workshops take a few hours, involve some healthy discussion, and most importantly provide us with clear consensus on what path to take. All user stories that are affixed to the wall under the “MUST” sign are in. Those in the “COULD” camp are out and those in the “SHOULD” camp will only make it in after higher priority “MUSTs” are completed.

Physically moving cards around gives everyone a chance to participate and seeing a features prioritized in this way is usually much more impactful than using a tool like Jira. That can come later as sprint planning adds a level of refinement that is missing from this initial exercise. As a parent, I will tell my children “You are all my favorites,” but in the world of digital product building, this should not be the case. We must ruthlessly prioritize to make a product truly lovable, even if that means releasing something that only conveys the essence of the bigger vision yet to come.

[1] Apptentive, “How many Mobile Apps are actually used”